by Krister Vasshus

In the Norwegian language one can, for the most part, recognise a place name on how it is formed as a «word». They may be words that describe topography, such as Vik (‘bay’) or Haugen (‘the mound’), or words that describe human activity on the place, such as Åker (‘field’) and Smia (‘the smithy’).

Place names are often compounds consisting of several words, such as Straumvika, Haugstad, Brunåker, Smiehagene. Some words that were used as terms for different kinds of settlements have even developed into a sort of suffix that we mostly see in place names, such as –tveit, –stad, –rød and –heim.

Imperative names

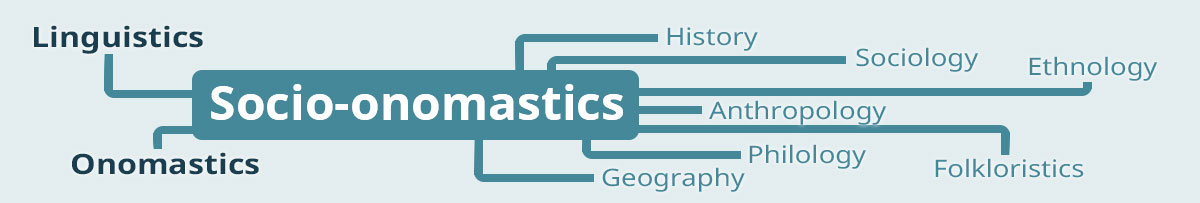

Our brains have a whole lexicon designated for names in our landscape. But in some cases names look different from the pattern we are used to. One example of this are imperative names such as Kikut and Bilitt. These names are compounded with a verb in the imperative form followed by an adverb. Hence Kikut means ‘take a look outside’ and Bilitt means ‘wait/rest a while’. This seems odd to Norwegians because place names are grammatically and syntactically close to nouns in our speech, whereas these names seem more like a verbal phrase.

As a type of placenames, however, the imperative names are not so uncommon, and exist in both Danish and Swedish as well. These names are for the most part a south-eastern Scandinavian phenomenon, and in Norwegian terms almost all these names can be found within the eastern Norwegian dialectal area.

More than one word

It is not uncommon to find Norwegian place names consisting of more than one word. Some of these feel perfectly normal, such as Austre Haugland (‘eastern mound-land’), Ytste Vika (‘the outermost bay’) and Gamle Grindebue (‘the old gate cottage’). The first word is always an adjective describing position, size or age. However, names like De ukvilte åsene (‘the unrested hills’), Den lange renna (‘the long run’) and Det lisle veirehovudet (the little ram’s head’) are not typical. In fact, most of these names are restricted to Telemark and Agder.

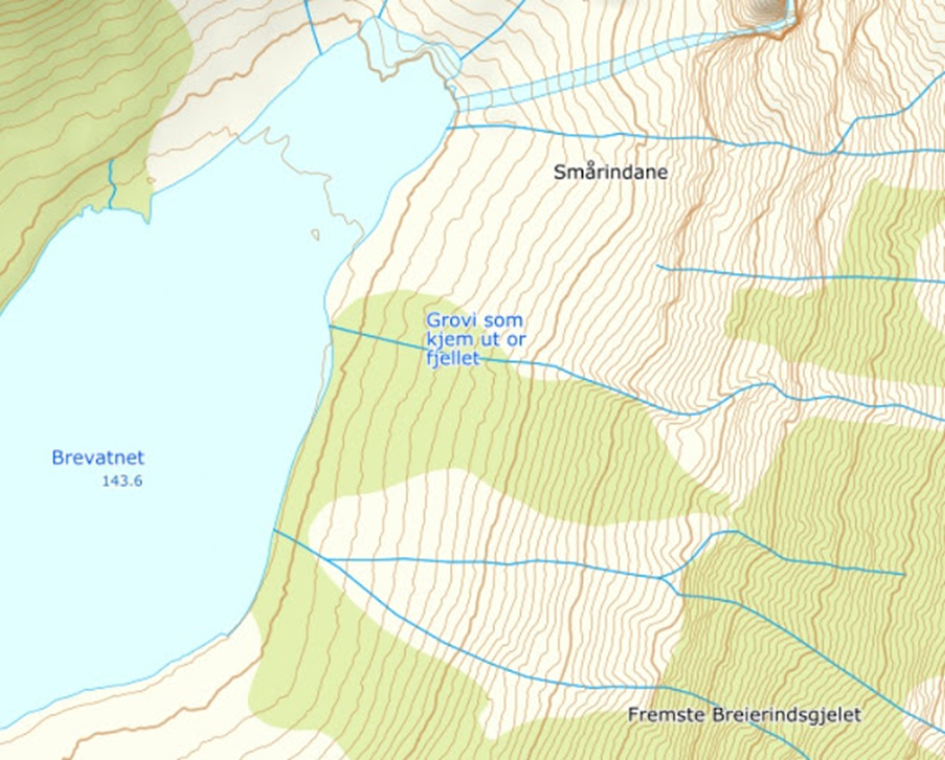

As soon as names consist of more than three words, Norwegians will generally feel it as an odd name. But such names can still be found in Norway. In Fjærland there is a stream named Grovi som kjem ut or fjellet (‘the stream that comes out from the mountain’). If we were to follow common naming patterns in Norwegian, a more suitable name could be *Fjellgrovi (‘mountain stream), but for some reason people in Fjærland have felt it important to point out that the stream comes out from the mountain.

Similarly, we find the name Den lange Haugen austmed vatnet (‘the long mound on the east side of the lake’) in Vinje. These names seem more like descriptions than actual place names, but if there are no other names for these places, such descriptions can become fixed and start functioning like other place names in daily speech.

A place name is in some ways a linguistic agreement between locals on how a place is to be denoted, and names therefore follow patterns of naming that a linguistic community (subconsciously) agree upon. But in the larger Scandinavian language continuum, we can see differences in what these agreements are. As we have seen examples of in this blogpost, some can be very locally restricted, and others form larger distribution patterns.

Further reading:

- Wohlert, Inge, 1960. Imperativiske Stednavne. I: Ti Afhandlinger: Udgivet i anledning af Stednavneudvalgets 50 års jubilæum, s. 63-95. (Navnestudier nr. 2.)