by Birna Lárusdóttir

Reading the landscape

“Children learned the alphabet of the landscape before and at the same time as they learned the alphabet of the book.”

This comment, in a place-name record put together in 1994 by Lúther E. Gunnlaugsson, farmer at Veisusel in Fnjóskadalur in northern Iceland, indicates that in Iceland in previous times, the ability to read the landscape, not least on the basis of place-names, was thought to be important. Each place-name represented a letter or sign, as in an alphabet, and as such, was part of a bigger whole.

Lúther’s comment fits well with well-known theoretical ideas about landscape and the marks that humans make on/in it. Scholars have, for example, compared landscape to a text in which writing, reading and literacy are implicit, and also to a palimpsest manuscript – a manuscript whose text has been scraped off and written anew with new ink. In this way, landscape, along with the place-names in it, is multi-layered, constantly changing and often complex. At the same time, it is necessary for those who live in and interact with particular places to be able to read it, or read out of it – to understand what place-names referred to, and what kinds of meaning they contained.

Place-name knowledge in past times could be an indicator of an individual’s status within a particular group, and it could enable children to accomplish tasks or work that carried with it a certain responsibility. Thus, in a place-name record for the farm of Brekka in Svarfaðardalur in northern Iceland, we read how adults had names for every landscape feature at their fingertips: “…each hill, gully or cliff … on every upland heath between Bakkadalur and Holtsdalur.

These place-names were necessary for boys to know if they hoped to become a shepherd, because otherwise it could be difficult if, for example, the dairy-women asked where the ewes had been found, and if he could not identify the place by name then he was an idiot and would be laughed at by them.” Aged nine, having accompanied his uncle up on the heaths searching for sheep, the author of these words had become a competent shepherd who was knowledgeable about place-names in the area.

Children as authors

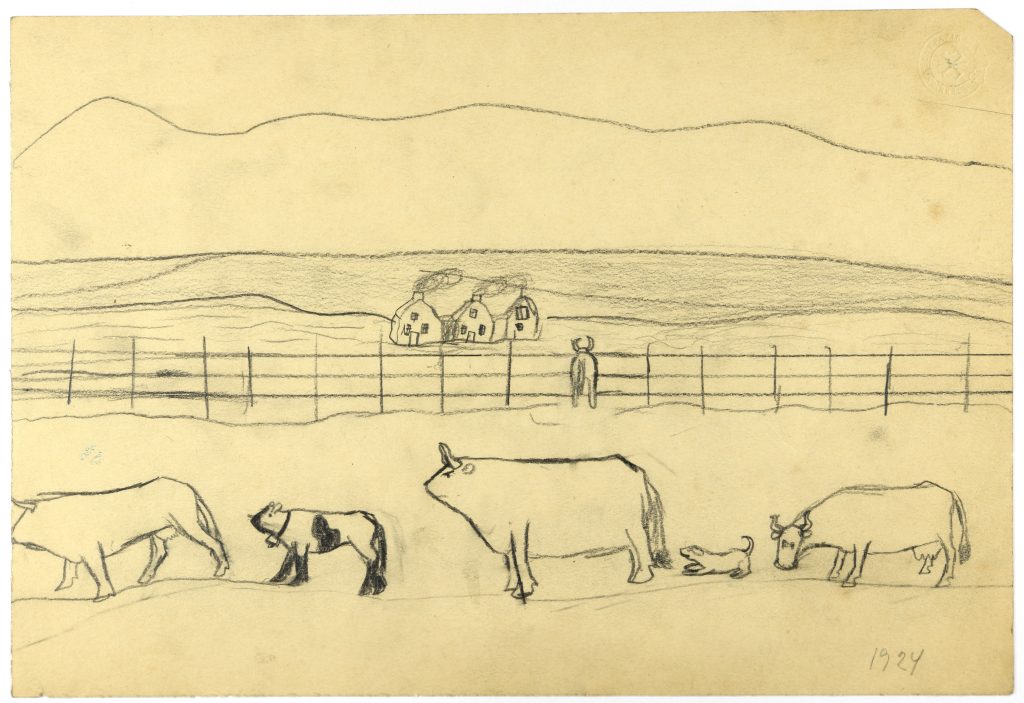

Children were not only passive readers of the landscape but also active authors. There are various hints that suggest this in the place-name records. The informants in the records had generally reached old age when the place-names were put down in writing but were happy to go back in time to their early years when they were recalled.

There are examples of ruins of shepherds’ huts in outer meadows that had names such as Markúsarkofi, Bensagerði and Rönkukofi, all most likely named after children who looked after the sheep, possibly by other children. Other examples of hut names include Bræðraborg (Brothers´ Butte), Krummastaðir (Krummi´s farm or Raven´s Farm) and Barnabaðstofa (Childrens´ living room).

Sites of play were probably the most common places that children named: these were places that were central to their early world but did not have much significance in the daily life of adults. Examples of these may include Gullatóft at Austdalur in Seyðisfjörður in the east of Iceland, and Leggjabú at Dalbær in Hrunamannahreppur in southern Iceland: both names refer to toys directly.

There are other examples where play-sites were given farm-names, e.g. at Litli-Galtardalur on Fellsströnd in western Iceland where kids built “houses and halls, sheep-pens and fences” all around a certain hill. Fögruvellir (Fair Grounds) was nearby, as was Vallabú (Valli´s farm), “under a grassy overhang” – so-called because a boy called Valli built a structure there. At Austurhlíð in Eystrihreppur, southern Iceland, at a place called Kirkjulundur (Church Grove) there was a fenced-off plot where children buried dogs, cats and other animal friends. There was even a little church that the children had built: inside there was space for one person. These are all intriguing indications of how children named places to create a space for their games: they built their own world on the basis of various ideas taken from the adult world, adapted to their own sphere and rules.

Sometimes children’s place-names are not paid much accord in the place-name records. An example of this is found in the record for Staðarhraun in Mýrar in the west of Iceland: a certain channel that children called Kjóamýri because of Arctic skua attacks (kjói = Arctic skua) is mentioned, but the informant makes it clear that that name disappeared from use as soon as the children had grown up.

At Landakot on Vatnsleysuströnd on the Reykjanes peninsula there is a description of a boggy area called Móar where there were bare patches of earth and rocks to which children gave “various names, which hardly count as place-names.” Unfortunately, these names were not recorded.

In both of these examples we can see the assumption that place-names used by children were not thought to be of much significance: maybe the names had not been passed on to others or become established in the adults’ language, likely because they were only used within the children’s group and therefore the chances of them becoming fixed were smaller.

Another example, though, from Vatnsleysuströnd, might point to a contrasting idea: that children themselves were also part of the place-naming process: there, children came up with new names for places that already had names – thus they began to call “Síki” (Canal) by another name, “Sílalækur” (Small Fish Creek), and the ruins of the old farm-house at Stóru-Vogar “Rústir” (Ruins). Both of these names seem to have survived.

All of the examples in this paper derive from place name registers preserved in the archive of The Árni Magnússon Insitute, Iceland. Most of them are accessible online at: www.nafnid.is

This paper is an English translation of the Icelandic Stafróf landsins: Örnefni barna that appeared on the Árni Magnússon Institute web page in November 2020. Translation by Emily Lethbridge.