By Alexandra Petrulevich

The upcoming volume “Digital Spatial Infrastructures and Worldviews in Pre-modern Societies” published by ARC Humanities Press introduces nine Nordic research infrastructure outputs with spatial focus: Norse World, Mapping Saints, The Icelandic Saga Map, Nafnið.is, TORA: Topographical Register at the National Archives of Sweden, The Swedish Digital Place-name Register, The Swedish Open Cultural Heritage, and DigDag: A digital atlas of the historical and administrative geography of Denmark. Research infrastructure here is understood as carefully curated research data collections made available for researchers, students and the general public for exploration and analysis.

This segment of research outputs has grown immensely over the recent decade in the Nordic countries. There are many reasons for this development, for instance, researchers’ interest in spatial dimensions of various materials such as place-names, early modern inventories and cadastral maps, medieval literature and art etc., and interdisciplinary methodology combining traditional and digital methods as well as availability of specific research funding calls.

Apart from presenting the resources and the data they offer, the chapters of the volume include example studies showcasing the potential of these newly developed spatial infrastructures for research as well as practical applications of digital methods.

The spatial focus of the aforementioned projects implies, quite unsurprisingly, that many of them deal with place-names, modelling of place-name data or place-name databases in one way or another. This is a welcome development in the field of spatial humanities where collation and processing of name data traditionally received little attention.

In the realm of the digital, place-names are seen as mere attributes, an almost arbitrary addition to the core values in the digital gazetteer model, coordinates and feature type, widely used to both define and describe any location in a spatial database. This volume provides several examples of how geocoded humanities data challenge this model and in what ways the model can be adapted and further developed in accordance with the project’s ambitions and needs.

For instance, Peder Gammeltoft re-considers the mainstream approach to handling place-name data in digital gazetteers in chapter 6. Because place-names occur in etymologically and otherwise related clusters and because one and the same locality can be associated with multiple names or name forms, Gammeltoft introduces the concept of a unique place-name identifier and thus a novel approach to structuring place-name data in databases.

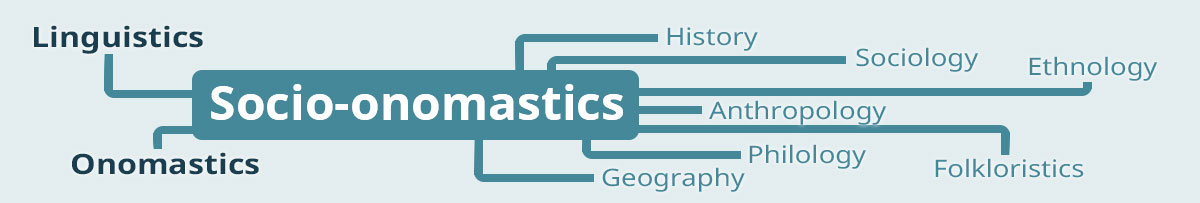

Another example is chapter 11 where I also make a contribution to reform the mainstream gazetteer structure and its approach to place-name materials. Chapter 11 offers both theory and methodology for dealing with place-names and place-name variants in spatial research infrastructures in analytically meaningful way—facilitating not least socio-onomastic studies of name variation in texts of different genres. These two chapters—as well as related studies in chapters 1, 10 and 12—offer innovative approaches to place-name modelling that captures the essence of place-names and that would be of interest to anyone interested in developing a spatial dataset from scratch.

The volume Digital Spatial Infrastructures and Worldviews in Pre-Modern Societies edited by Alexandra Petrulevich & Simon Skovgaard Boeck will preliminarily be published by ARC Humanities Press on April 10.