by Krister Vasshus

Trends in naming can be classified in several ways, and over the course of 30 years, we can see that there have been several trends in the Norwegian naming material. When Norwegian parents give names to their children, they have a large pool of names to choose from, but statistics clearly show that the chosen names follow certain trends. In the following, I will give a short overview of these trends.

Close-up vowels

Names with two vowels next to each other fall into two categories. They can either be with a diphthong or with two syllables. Øystein, Aud and Heidi all have diphthongs, and are fairly common. Names where two vowels next to each other are pronounced with two syllables, however, constitute around half of the top 10 given male names between 1990 and 2005. This trend has since been less important (two-three names on top 10 male names between 2018 and 2020), and it also took a while before this phonetic trend constituted half of the given names for women, between 2010 continuing to 2020.

Women with vowels, men with consonants

Over the last 15 years, all top 10 woman names ended with a vowel (with the exception of Ingrid on place 10 in 2020, although this name is pronounced [iŋ:ri:] or [iŋg:ri:] in Norwegian, still ending with a vowel). After 2010, seven of the top 10 female names ended with a.

Between 1995 and 2015, all top 10 names for men ended with a consonant. This trend is still valid, and both for 2016 and 2020 the only name on this list ending with a vowel was Noah/Noa. After 2000 the o-ending has become more common in boy names, clearly influenced by southern European names like Theo and Hugo.

When it comes to consonants, we can clearly see that l, m, n and r are very popular in names. On the top 10 list for boy names in the first decade of this millennium, these sounds represented half of all the letters, and 70% of the letters in girl names. In later years, we also see hints that voiced full stops (b, d, g) are viewed as feminine and voiceless full stops (p, t, k) are viewed as masculine. After 2000 there has been more vowels in girl names and more consonants in boy names.

Length

After a period between 1970 and 2000, where names, especially women’s names, had been long, the most popular names became shorter. Mostly this was because parents chose names with fewer consonants, as the number of syllables has been stable. Aleksander and Bjørnar has the same number of syllables as Emilie and Lea, but there is an obvious difference in length in the names. Some long names are still popular, and the tendency is that parents either use long names or short ones.

Stress on the first syllable?

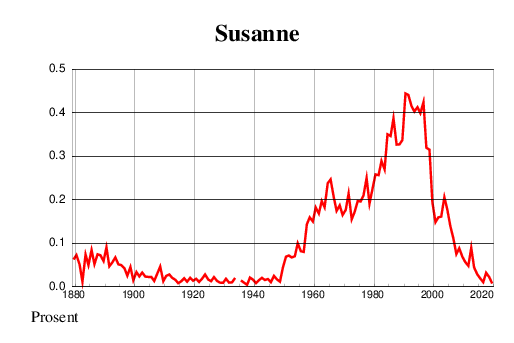

Nordic names, like most other words in Scandinavian, have stress on the first syllable. This was also the case for Nordic versions of names with foreign provenance, such as Anna, Thomas or Line. By the 1990s, about half of the girls and one third of the boys got names with stress on the second (or third) syllable, like Susanne and Karoline. This trend started in the 1960s for girls and in the 1980s for boys. After 2000, names with stress on the first syllable became more common again, particularly for the boys. After 2010 only about 2 of the top 10 boy names had stress on the second or third syllable, but for girl names it was 3-4 of the top 10.

Nordic or biblical names?

Nordic names were dominant on the top 10 list until the 1940s, when these names gradually decreased in number. But the number of Nordic names on the top 50 lists for both girl and boy names has increased somewhat since 2010, from 4-5 names for both genders to 11 girl names and 8 boys names in 2020.

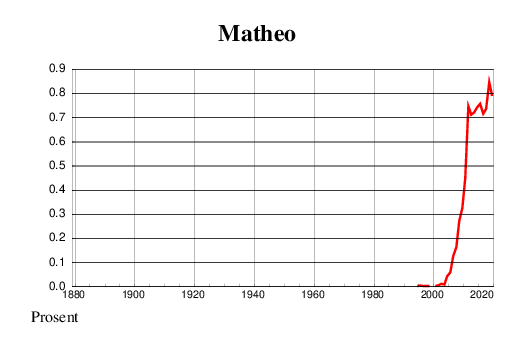

Biblical names have been increasingly popular since 1990, and many of these names have characteristics that fall into some of the abovementioned traits, like close up vowels (Naomi, Matheo) and girls names ending with a (Lea, Sara, Rebekka). Overall, there is a tendency of a bigger spread in naming. The most popular names are given to fewer individuals, and many parents seem to want their kids to have original or rare names, or at least what the parents view as original and rare.

One thought on “Naming trends in Norway”