by Peder Gammeltoft

Names carry profound meaning, serving as personal identifiers while also reflecting broader cultural, familial, and societal influences. Data from the Danish Link-Lives project, offers a unique opportunity to explore how personal names reveal patterns of migration, identity, and cultural adaptation. The census includes families that migrated to Argentina, had children born there, and later returned to Denmark, reflecting a rich story of transatlantic movement. The analysis of these names offers insights into how families navigated between Danish and Argentine cultures, particularly through the naming of their children.

Personal Names and Migration: What’s in a Name?

Migration is not just about moving from one country to another – It involves the transfer and negotiation of identities, traditions, and cultural norms. Personal names are a powerful reflection of this process, capable of signaling an individual’s cultural roots, religious beliefs, or even social aspirations. In the case of Danish families who moved to Argentina and then re-immigrated to Denmark, the naming of children born in Argentina can tell us a great deal about how these families balanced their Danish heritage with the new cultural environment they encountered in Argentina.

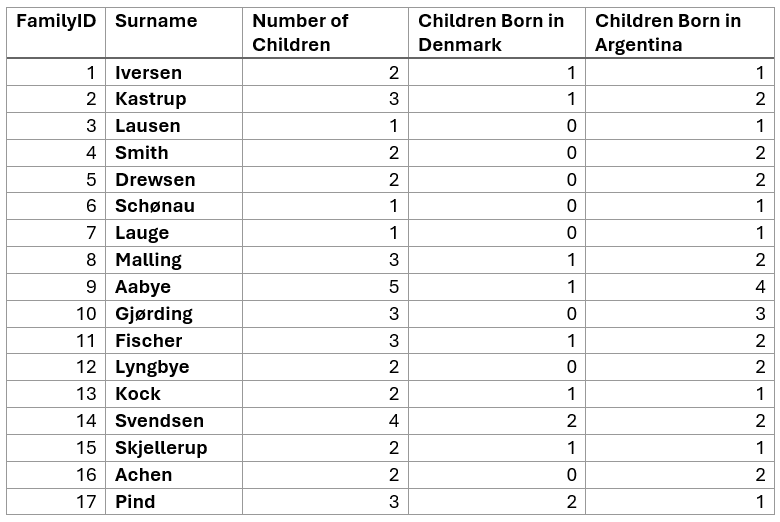

The Link-Lives Project, is part of a broader effort to link historical records of individuals across generations, including censuses, church records, and civil registries. The project’s aim is to create a connected and accessible database for researching personal histories. The 1901 census in the Link-Lives project includes 17 households, each containing a mix of children born in Denmark and Argentina. Among these families, there are 41 children, 29 of whom were born in Argentina and 12 in Denmark. By analyzing the first names of these children, we gain insight into how these families navigated their cultural identities, particularly in relation to their stay in a part of the Spanish-speaking world, Argentina. Although the material is small, there are clear tendencies.

A Closer Look at Family Composition

A breakdown of the families included in the dataset, showing how many children were born in Denmark versus Argentina:

Cultural Identity Through Personal Names

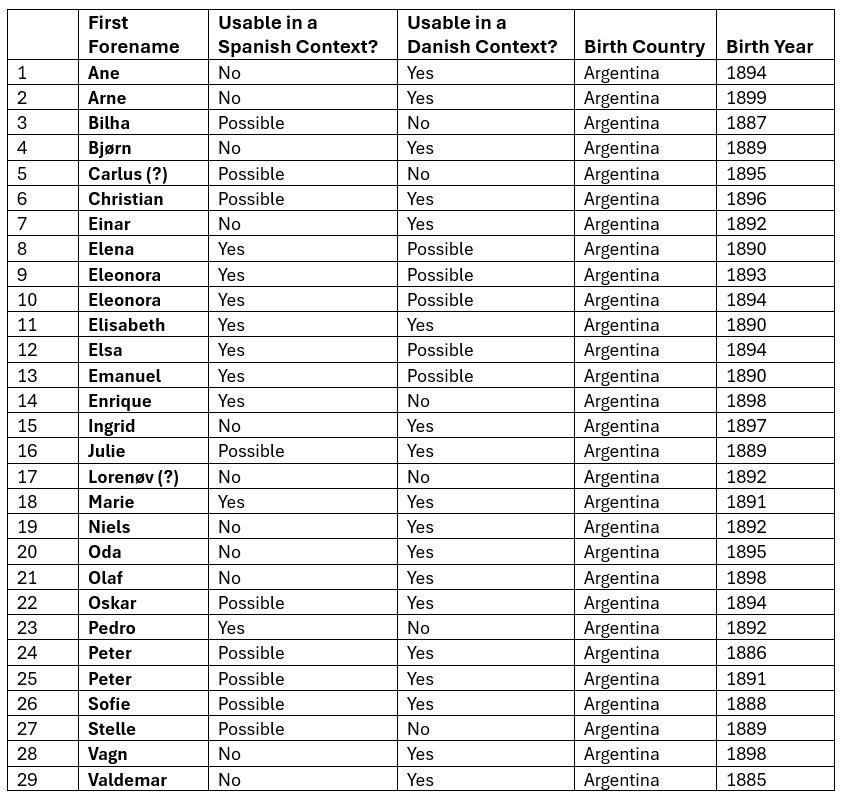

The study of names in this dataset reveals three distinct categories based on how well a child’s name would fit into a Spanish-speaking country like Argentina. These categories – formally usable, possibly usable, and not usable – help us understand how families integrated (or resisted integration) into Argentine society through the naming of their children.

- Formally Usable in a Spanish-speaking Context: Names that would easily be recognized in Argentina, either because they are common in both cultures, or have Spanish equivalents.

– For instance, among the children born in Argentina, names like Elena, Eleonora, Oskar (Oscar), Pedro, and Enrique would have been very familiar in both Argentina and Denmark. Of the 29 children born in Argentina, 9 had names that fall into this category. These names reflect a potential desire for integration into the local culture, possibly making it easier for children to fit into Argentine society. - Possibly Usable in a Spanish-speaking Context: These names are less common but still recognizable in Argentina.

– Names such as Christian, Ingrid and Peter are familiar but less frequent in a Spanish-speaking context. Nine of the Argentine-born children had names in this category. These names suggest that the family retained a connection to Danish traditions while also choosing names that would not be entirely out of place in their new environment. - Not Usable in a Spanish-speaking Context: Names that are Danish and would likely have stood out in Argentina.

– Examples include Arne, Inger and Valdemar, which are typically Danish and would be unusual in a Spanish-speaking country. Eleven Argentine-born children had names in this category. These names likely reflect a stronger attachment to Danish identity, suggesting that the family wanted to maintain their cultural roots despite living abroad.

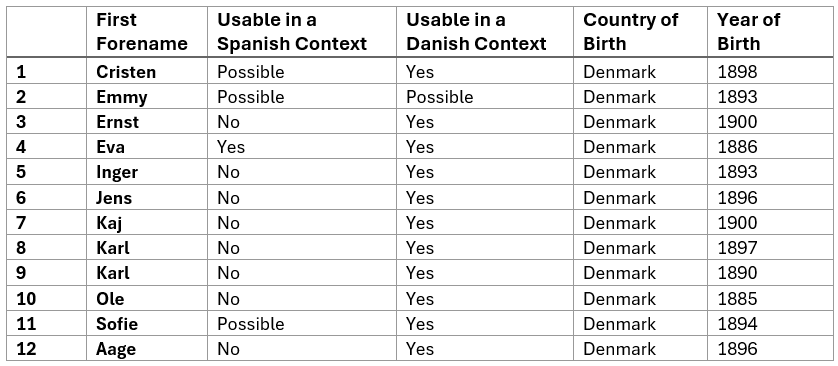

Dataset Breakdown: Children’s Names by Birth Country

Let us look at children’s first forenames, birth countries, and whether their first forename would work in either a Spanish-speaking or Danish-speaking context:

Conclusion: The Significance of Name Research in Migration Studies

The study of personal names within the context of migration provides a unique lens through which to explore cultural identity. For families that migrated to Argentina, naming their children involved a balance between maintaining their Danish heritage and integrating into Argentine society. Children with names like Elena or Pedro may have been better able to navigate both cultural worlds, while those with distinctly Danish names may have faced greater challenges in fitting in.

For the children born in Denmark after their families’ return, the predominance of traditional Danish names suggests a desire to reclaim or reinforce their Danish identity. These children would grow up in Denmark, and their names reflect a re-rooting in their home country’s cultural norms. The choice of names illustrates how these families viewed their identity – both abroad and at home.

Literature

- Hornby, Rikard, 1978. Danske personnavne. København.

- Link-Lives: https://link-lives.dk/

- María Bjerg, 2019. Brudte bånd. Immigration, ægteskab og følelser i Argentina mellem det 19. og 20. århundrede. Bernal.

- Meldgaard, Eva Villarsen, 2002. Den store navnebog. København.

- Tibón, Gutierre, 2002. Diccionario etimológico comparado de nombres propios de persona. Mexico City.