by Birna Lárusdóttir

The arrival of modernity in a remote valley

Iceland is famous for its abundance of water resources which have in many cases been harnessed to generate electricity. Although often claimed to be sustainable this has not come without sacrifice. The first hydropower station in Iceland was built in Fljót, N-Iceland in the 1940s to generate electricity for the rapidly growing herring industry in the neighbouring town of Siglufjörður.

The location was favorable for such a project: a deep valley nearly closed off at its furthest end by an old landslide, making it relatively easy to build a dam. The level of the reservoir rose quickly and the bottom of the valley, described as beautiful hay meadows with clear ponds and creeks, disappeared. Before all this, the so-called Stífla area (Stífla ironically translates as dam or blockage) was rich farming land, the home of many people most of whom lived on relatively small farms located uphill from the level bottom of valley. Many of the farms were abandoned in the years following the building of the dam and today none remain around the reservoir, only a few summerhouses and an old church (Knappsstaðakirkja) that had belonged to one of the earlier farms.

Although the ethics of the project were not discussed much at the time (at least not officially) this landscape intervention seems to have left deep scars on the community.

Conserving place names

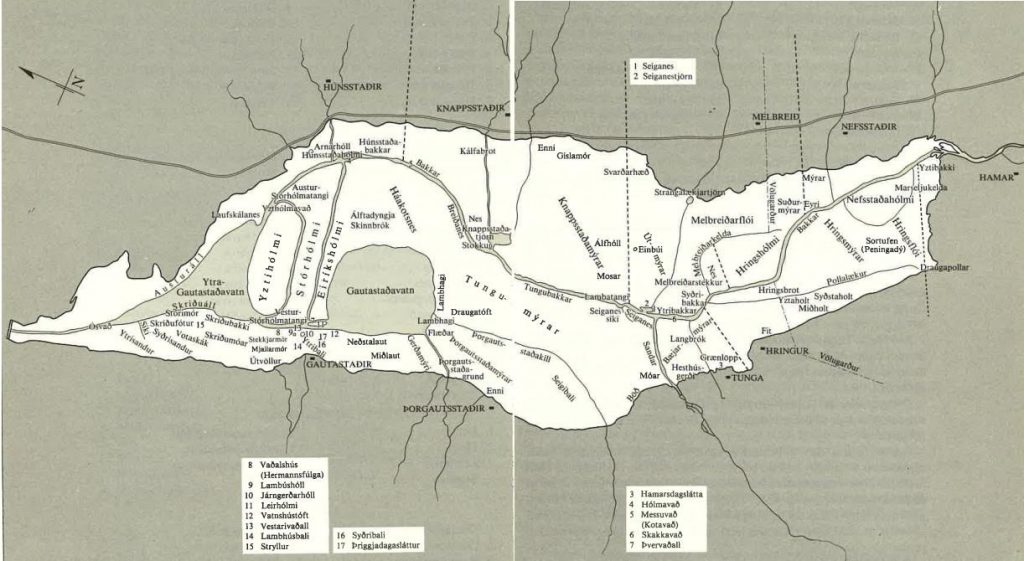

In 1983 an interesting paper about the vanished place names of the area was published in Grímnir, the journal of the Icelandic Place Name Institute. It was based on a map drafted by Páll Sigurðsson, who had lived in Stífla for decades. In the mind of the author, Þórhallur Vilmundarson, who was Head of the Place Name Institute at the time, the damage done to the landscape in Stífla was immense. He suggests in the paper that places which carry curious names should generally not be damaged. If there is no other alternative, place names ought to be registered and located on a map before the destruction of an area.

The vanished place names of Stífla show how it was the heart of a thriving farming community – mostly fertile wetlands, pastures and meadows on which the farms built their existence. Many of the areas carried names according to their nature (as wetlands), f.ex. Útmýrar and Hringsflói. Some of the names indicate the size of meadows and how long it would take to cut the grass on them (Hamarsdagslátta, Þriggjadagasláttur – in this case one and three days).

Many parts of the banks of rivers and ponds also had names (Ytribakkar, Skriðubakki, Bakki) and yet others paint a landscape formed by creeks and ponds (Austuráll, Laufskálanes, Lambatangi) – and humans/animals. There are also names of structures related to farming activities which vanished into the deep: Völugarður – an ancient turf wall, Melbreiðarstekkur – a sheep fold, Draugatóft – literally “Ghost ruin”. And at the bottom of the center of the reservoir lies Einbúi, the alleged grave mound of the slave of Nafar-Helgi, the main settler of the area according to the twelfth-century historical work Landnámabók, ‘The Book of Settlements’.

The value of names

The names represent different values and draw up a different picture of the landscape than that which one builds up through objective description of natural elements or vegetation. Vilmundarson’s position on how place names should be valued and protected or mapped in the context of construction or other landscape change caused by humans contributed to discussion in Iceland on nature conservation and raised questions that seem to be still critical today – perhaps even more so than when the paper was published forty years ago. What happens to place names when great landscape-change takes place and what are they really worth? What is the difference between experiencing place names “in situ” – in their own settings, or reading them from a map or some other textual record?

Many hydropower plants have been built in Iceland since the one in Fljót although none of them has destroyed inhabited farmland. In some cases, place names have been mapped specifically before disappearing, f.ex. in the area which vanished under the Hálslón reservoir near Kárahnjúkar north of Vatnajökull glacier. In many other cases landscape change induced by humans takes place without any regard to place names – f.ex. through forestry, the building of large scale factories and the expansion of urban areas.