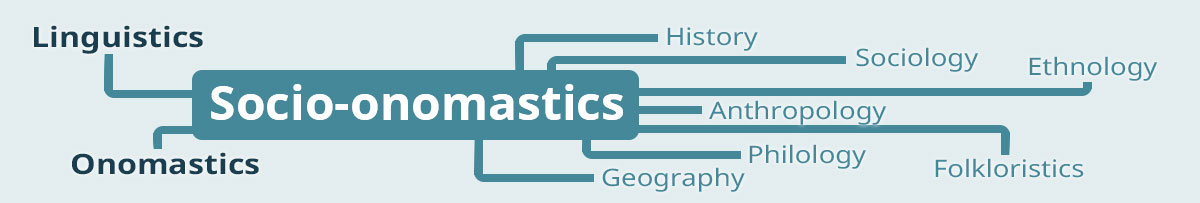

By Alexandra Petrulevich

Today, 25 February 2022, the day after Russia launched massive invasion of Ukraine, it is immensely difficult to think about anything else or engage in any other activity than following live broadcasts, news and analyses of all sorts and checking up on Ukrainian friends and their families. Official media channels in Sweden (and the rest of Europe) and Russia present strikingly different narratives about the war, so different that I sometimes wonder if they are describing the same chain of events.

The flow of audio and visual information I digested these past two days contains lots of place-names; there are maps of Ukraine with all the major cities marked, mentions of the journalists’ or interview persons’ whereabouts as well as lists of air strikes targets and casualties. The name use across the two mediaverses, the Swedish/European and the Russian one, differs as well; in the West, the official Ukrainian names in transliterated form are preferred in most cases, Lviv (Львів), Kharkiv (Харків), Kyiv (Київ) and Ivano-Frankivsk (Івано-Франківськ), while Russian media make use of Russian equivalents Львов (Lvov), Харькoв (Kharkov), Киев (Kiev) and Ивaно-Франковск (Ivano-Frankovsk). In Sweden, there are however exceptions: those Russian names that have a long tradition in the Swedish language such as for instance Kiev, Odessa and Tjernobyl are used alongside transliterations of Ukrainian names (1). What is the status of the names scientifically and politically?

Exonyms and endonyms

The situation of one place bearing multiple names is generally very common and definitely a rule rather than exception in language contact areas. Historically prominent places tend to have multiple parallel names, for instance, Vienna, Vienne, Vena, Wiedeń, Víden, Villaco etc. used to refer to the capital of Austria, Wien, in different European languages. A typical explanation for such parallelism is that names are usually loaned in adapted form, for instance, due to pronunciation difficulties. In other words, when loaned, the name undergoes changes in accordance with the rules of the recipient language system. Moreover, the adaptations in question can be based both on the oral and written forms of the name, the English Warsaw for Warszawa being an example of the latter.

The names of geographical features in languages other than the official language(s) spoken in the area where the feature is situated are called exonyms (2). Among the examples listed in this section, Warsaw, Vienna, Vienne, Vena, Wiedeń, Víden, and Villaco qualify under the definition. The “opposite” of exonyms are called endonyms, defined as the names of places and other features in the official language of the area, for instance Wien in German and Warszawa in Polish.

The leading international body working for standardization of place-names worldwide, the United Nations’ Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN), has issued a policy recommending the UN’s member states to promote the use of endonyms and minimize the use of exonyms internationally (2).

Endonyms in practice

In theory, it is a pretty straightforward recommendation. In practice, figuring out the status of the different names can give a slight headache. Most states are multilingual today and the languages spoken within their borders enjoy different rights.

In Finland, both the Finnish Helsinki and the Swedish Helsingfors are endonyms because both languages have an official status. Thus, both forms can be used internationally according to UNGEGN’s recommendation mentioned above. However, the Finnish endonym Helsinki is preferred in most international contexts.

Another typical complication concerns names in minority languages and indigenous languages. There is only one official language in Sweden, Swedish; however, there are no less than five minority languages in the country, Finnish, Sami, Romani, Yiddish, and Meänkieli. Moreover, place-names in Sami, Meänkieli, and Finnish are protected by the Swedish cultural heritage law and are to be included on road signs and maps in multilingual areas.

But what is the status of names in a minority language in the exonym vs. endonym debate? There has been a push to give the names in official minority languages an endonym status (3: 21, footnote 4: “differing in its form from the name used in an official or well-established language of that area”), but the official UNGEGN definition in the Glossary of Terms for the Standardization of Geographical Names does not yet unambiguously accommodate such an interpretation (2).

Languages in Ukraine

According to the constitution, Ukrainian is the only official language of the sovereign state of Ukraine (4, article 10). Russian – alongside other non-specified minority languages – is guaranteed protection and free use. Historically, Ukraine was divided between Austria-Hungary and the Russian Empire; the imperialist fear of Ukrainian independence led to Russia prohibiting publication of Ukrainian in the latter half of the eighteenth century (5).

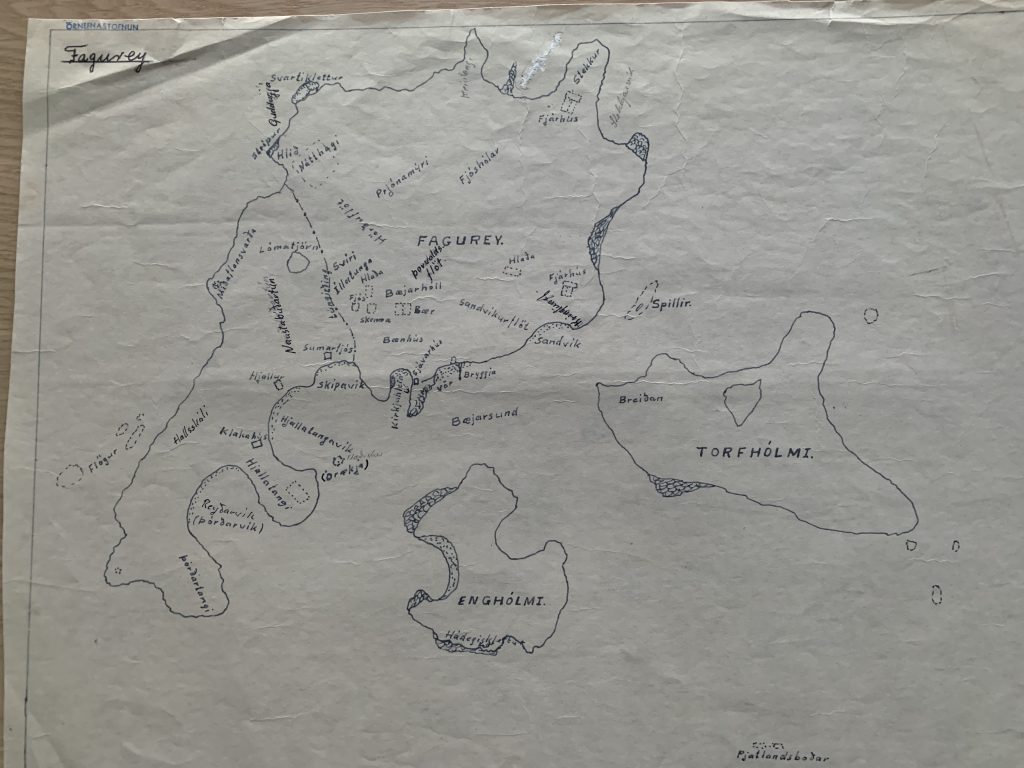

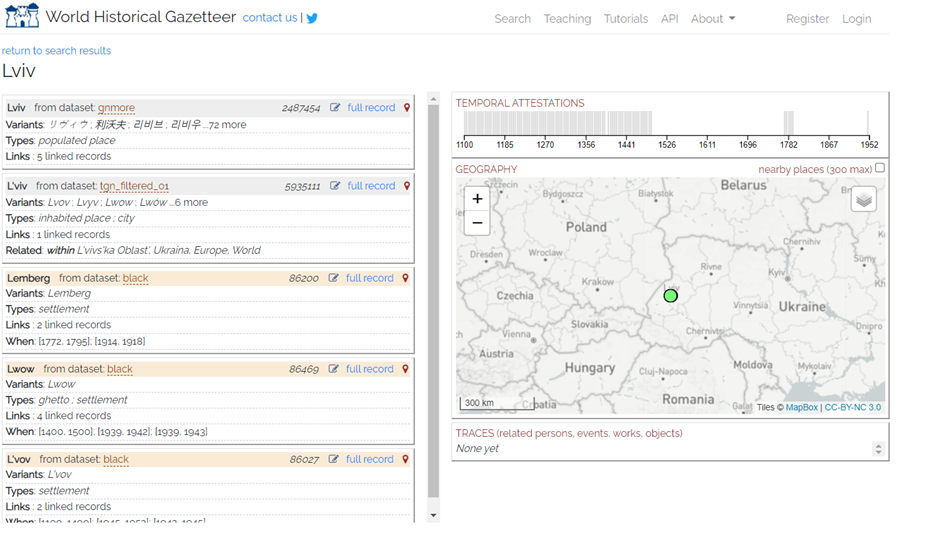

It is important to acknowledge that Ukraine was (and still is, although another palette of spoken languages is in place) a highly multicultural society where Polish, German, Romanian, Hungarian, Yiddish, Hebrew, Armenian etc. were spoken alongside Ukrainian and Russian. For this reason, there are many more historical names of Ukrainian cities to choose from. For instance, the city of Lviv – Lvov in Russian – used to be called Lemberg in German and is still referred to as Lwów in Polish (see the figure from the World Historical Gazetter).

Transition to Ukraine endonyms

So, Lviv or Lvov or both? The only conclusion to be drawn from the above is that transliterations of Ukrainian names should be used in other languages according to the aforementioned UN’s place-name policy recommendation. Lviv, then.

The Swedish language council Språkrådet still sees both the exonym Kiev and the Swedish transliteration of the Ukrainian name Kyjiv (the form Kyiv above is an English transliteration) as equivalents because a sudden change from the established name to a new one might complicate readers’ or listeners’ understanding. However, the recommendation is to adopt the Ukrainian transliteration “when the time is ripe” (1).

In the light of the current events when Russian bombs are falling all over Ukraine, the transition towards Ukrainian endonyms will most likely accelerate dramatically.

Updated March 3rd 2022

References

- https://frageladan.isof.se/visasvar.py?sok=kiev&svar=79953&log_id=905832

- Glossary of Terms for the Standardization of Geographical Names (Revised)

- Revision proposed by a Joint Meeting on Geographical Names, Prague 2003, referred to in Raukko, Jarno, A linguistic classification of exonyms, in: Jordan, Peter, Milan Orožen Adamič & Paul Woodman (eds.) Exonyms and the International Standardisation of Geographical Names: Approaches towards the Resolution of an Apparent Contradiction (Wiener Osteuropa Studien, 2007).

- The Constitution of Ukraine

- Plokhy, Serhii, 2017: The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. New York: Basic Books.